THE ECONOMICS OF DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY

When images were made using film clients understood that film, processing, proofing, printing and Polaroids would all be appearing on their invoice. With a reusable memory card and delivery by electronic means it is therefore some people’s conclusion that these production costs have been negated. Everyone appreciates the benefits in turnaround from a digital workflow but the industry will be heading down the tubes unless many more understand the economics:

1. Capital costs – When a photographer bought a professional film camera this was a seriously long-term investment, lenses would be added and spare bodies would follow but these cameras were going to be around for a long time. Until I moved to digital I still regularly used cameras that I had owned for 10 to 20 years. Improvements in imaging technology were made in film emulsions and every photographer benefited from this each time they bought a roll of the latest type, which was paid for by the client. Today with digital cameras we all have to stay ahead of the curve by buying into better sensor technology, meaning expensive new cameras are now bought at regular intervals.

2. Processing costs – Creating a digital image from a RAW file requires equipment and software both of which, unlike the equipment in a darkroom, require constant upgrading. To be clear here I’m not talking about the variety of retouching, CGI or post-production that may be required (after all the photographer may not be doing this in-house), I’m talking about getting from your camera to a proof; download, storage, some basic adjustments and corrections to enable upload for preview.

3. Delivery costs – Just because you don’t courier a transparency any more it doesn’t mean there are no delivery costs. Broadband connections, FTP sites and the equipment to use them all involve expense.

4. Storage costs – Paper storage pages for negatives or transparencies (which the client had already paid for) have been replaced by hard drives, DVDs and server space (which the photographer is now expected to pay for).

Lou Lesko’s book Advertising Photography credits Los Angeles based photographer Anthony Nex as the man who coined the phrase “digital service fee” or DSF which covers many of these expenses.

I believe that there is a very clear need for education here because these costs must end up on our invoices, like all costs in all businesses. Whether included in rates or as a separate fee, clients and new photographers (who are often far too keen to discount) need to be aware of the unavoidable cost of digital imaging. I will close with an example from the extreme end of the discounting scale that illustrates the need to educate both commercial photographers and commissioners of photography:

I once discussed a brief with a publicly funded organisation that needed a photographer to cover an event – the requirement was in two parts:

1. One shot of the national CEO getting involved in activities at the event, delivered fast for a press release.

2. Followed by “a large amount of stock images from the event to be used for future publicity” to be delivered later, after some editing.

The discussions went well and I provided a quotation, this was the email reply I received the next day – “Hi Stephen, Thank you for getting back to me. Unfortunately we won’t be needing you in this instance. You were competitively priced and I was very impressed with what you were offering. However, we had an offer for a young photographer to come along and do the event for free which we simply couldn’t turn down. I will keep your details on our system for future jobs if that is ok?” Discussion with colleagues has revealed that this is in fact quite commonplace and this raises some important points:

1. Working for free reinforces the misconception that digital photography has no cost and those who suggest it often exploit the myth that “the exposure will be very worthwhile”. I would suggest that a referral from a company who have no budget will only ever lead to more “work” from companies in the same sinking boat.

2. What about the other fixed costs of running the business, for example would someone who expects you to work for free be happy if you arrived on their premises without public liability insurance? After all if they are not going to pay you how on earth can you be expected to pay for insurance? If you do work without it both you and the “client” are taking big risks in a society where litigation is a way of life.

3. The most damaging aspect of working for free is the threat it poses to the sustainability of our industry – surely anyone who has a genuine interest in making a career out of professional photography will want to be starting out in a business with a future.

My response to the client was simple “I certainly can’t compete with that on price! However I remain confident that my 25 years experience enable me to compete on quality and service.” I stopped short of pointing out the real dangers he faces, not least of wasting a considerable budget running an event without making sure he will get high quality images delivered to specification within the agreed timescale. After all a photographer who will work for free probably values his reputation about as much as he values his work – the danger is that value gets confused with price.

In another example – Arts Council England’s site www.artsjobs.org.uk is hosting a brief for a commercial comission from CultureLabel.com who are – “looking for someone who wants to build their photography portfolio”. They claim – “Your work will have the highest visibility on CultureLabel.com, and we’ll provide a small fee to reimburse you for your time”.

Thanks for reading,

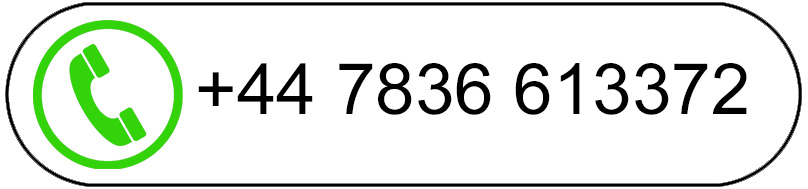

Stephen Potts

Belfast photographer and filmmaker

Leave a comment